Building a GPT-2 Tokenizer in Go

There are easier ways to spend your weekends. Building a GPT-2 tokenizer from scratch is not one of them. But somewhere between reading Karpathy’s “Zero to Hero”, benchmarking Go’s runtime behavior at 2AM, and debating whether my slice reallocation was “morally acceptable”, I fell down a rabbit hole.

This post is the story of how that happened: what I built, what broke, what I optimized, and what I learned about systems engineering by reconstructing one of the most universally used components in modern LLMs: the tokenizer.

The BPE Tokenizer

A tokenizer is the first step in almost every modern language model pipeline. Its job is simple in spirit but critical in practice: convert raw text into a sequence of integer IDs that a model can process. For example: "Hello world!" can be encoded as [15496, 995, 0].

These integers correspond to entries in a fixed vocabulary learned during model training.

Every request to a large language model whether for inference or training, goes through a tokenizer first. That makes tokenization part of the critical path for latency-sensitive systems like:

- inference servers

- chat applications

- streaming generation APIs

- real-time classification systems

If tokenization is slow, everything downstream is slow.

Most modern LLMs (GPT-2, GPT-3, GPT-4 class models) use Byte Pair Encoding (BPE) or close variants.

At a high level, BPE works like this:

- Start with raw text as bytes (values 0–255)

- Repeatedly merge the most frequent adjacent byte/token pairs

- Each merge produces a new token

- Continue until no more applicable merges exist

The result is a vocabulary of:

- single bytes

- short character sequences

- common substrings (e.g. “ing”, “tion”, “http”)

BPE is attractive because it:

- handles arbitrary UTF-8 text

- balances vocabulary size vs. expressiveness

- compresses common patterns efficiently

But it has a downside: tokenization is not just a lookup, it’s an algorithm. At runtime, a BPE tokenizer must repeatedly:

- scan adjacent token pairs

- check whether (a, b) is mergeable

- compare merge ranks

- apply the best merge

- update neighboring pairs and all of this usually involves thousands of pair lookups per chunk of text.

Why Rebuild a Tokenizer at all?

If one’s interested in LLM infrastructure, tokenizers are not optional. Most production tokenizers are treated as black boxes but that abstraction leaks quickly once we start caring about end-to-end latency, memory patterns, and streaming inputs.

I wanted to understand what was actually happening inside. So I rebuilt it - byte-pair encoding, vocab parsing, merges, greedy selection, token mapping, streaming semantics, all of it.

In Go.

Because why not.

The Goal

The goal wasn’t just to encode text. It was to build:

A streaming-friendly, GPT-2 tokenizer in Go, with exact round-trip parity.

I wanted:

- No hidden allocations.

- No unnecessary copies.

- Streaming support for chunked text.

- Benchmarks.

I quickly learned: this is way harder than it sounds.

The Underestimate: BPE is simple, right?

Before this project, I thought tokenization was basically:

- Load vocab.

- Greedily merge pairs.

- Done.

I was wrong. What’s usually hidden in subtext is that BPE merging is quite convoluted and involves:

- priority queues

- adjacency maintenance

- invalidation semantics

- versioning to prevent stale merges

- dealing with arbitrary Unicode byte sequences

- ensuring determinism

- avoiding pathological quadratic behavior

- and in streaming mode, dealing with chunk boundaries, which are an entire horror movie of their own

The First Win: Offline Encoder Working

The offline greedy BPE encoder was the first major milestone.

It worked. It matched Hugging Face.

It passed all round-trip tests.

It handled odd unicode, edge cases, and controlled merges correctly.

This gave me the confidence to start the real challenge - streaming.

Where Things Got Spicy: The Streaming Encoder

Streaming is not “offline but in chunks”.

Streaming requires:

- maintaining adjacency across chunk boundaries

- scheduling merges correctly even when pieces arrive out of order

- maintaining liveness invariants

- tracking live version numbers

- updating linked lists of token nodes

- dynamically adjusting a tail-reserve so merges don’t cross uncommitted boundaries

- rewriting heap candidates without invalidating active merges

This part of the project consumed weeks. I rewrote large sections and repeatedly reached states where invariants failed in unpredictable ways.

I hit issues like:

- stale heap candidates creating illegal merges

- cross-boundary merges misfiring

- node liveness drifting out of sync

- adjacency pointers failing in ways I wasn’t aware of

Eventually, I stepped back and realized something important:

Fully incremental streaming BPE is elegant, but the complexity quickly becomes the main thing you’re managing.

That was a turning point. The right move at the time for me was to stop, and optimize the naive streaming encoder instead.

The Optimization Journey

Once the incremental encoder was deprioritized, something magical happened. I could finally treat tokenization like an optimization problem, not a correctness war.

The naive streaming encoder is simple:

- break input into chunks

- run offline BPE on each chunk

- concatenate results

No cross-boundary merging but extremely practical. And most importantly, much easier to optimize.

A short detour on the benchmarking setup

All measurements in this post come from a single Go benchmark designed to reflect a realistic streaming tokenization workload.

At a high level, the benchmark:

- feeds the encoder 4 KB chunks of input text

- runs the streaming encoder end-to-end on each chunk

- measures wall-clock time, throughput, allocations, and allocation volume

Each benchmark was run:

- with GOMAXPROCS=1 to isolate single-core behavior

- using Go’s built-in benchmarking harness (testing.B)

- with CPU and memory profiles collected via pprof

Profiling the Naive Streaming Encoder: Where the Time Actually Goes

| Benchmark | Iterations | Time (ns/op) | Throughput (MB/s) | Bytes/op | Allocs/op |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BenchmarkNaiveEncodeStreaming_4KBChunks | 10 | 540,239,550 | 9.70 | 1,830,942,153 | 2,343,402 |

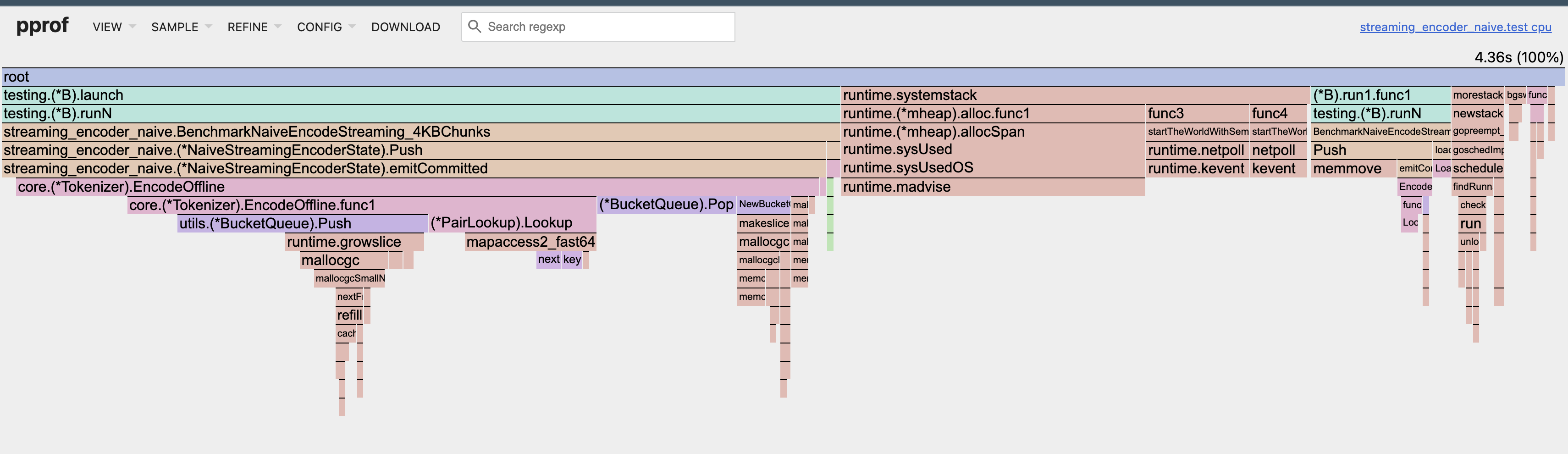

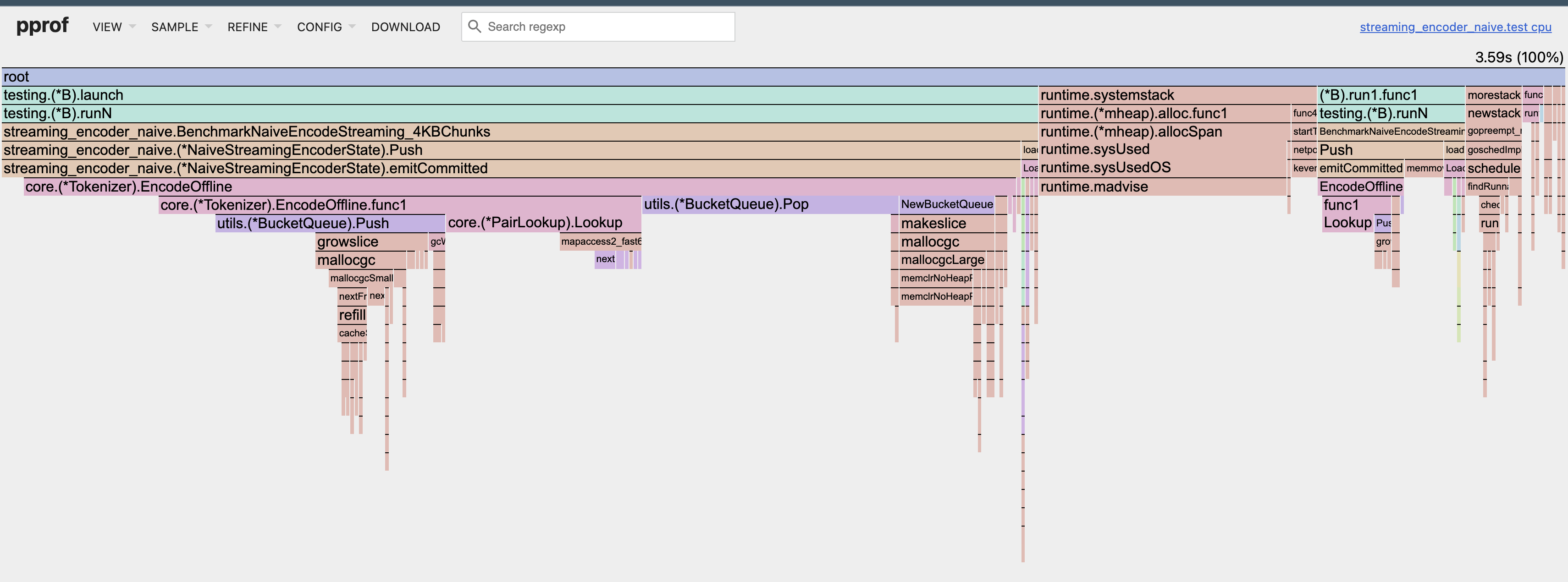

Here’s the CPU flamegraph from the baseline naive streaming encoder (4 KB chunks, single-core).

In the flamegraph above, EncodeOffline dominates CPU time, but the real culprits are two internal operations:

- Push/Pop for BucketQueue: responsible for ~35–45% of CPU time and millions of tiny allocations.

- mapaccess (pair-rank lookups): another ~20–25%.

Very little time is spent doing “useful compute” versus runtime overhead: hash-map lookups and allocation-heavy queue maintenance dominate the merge loop.

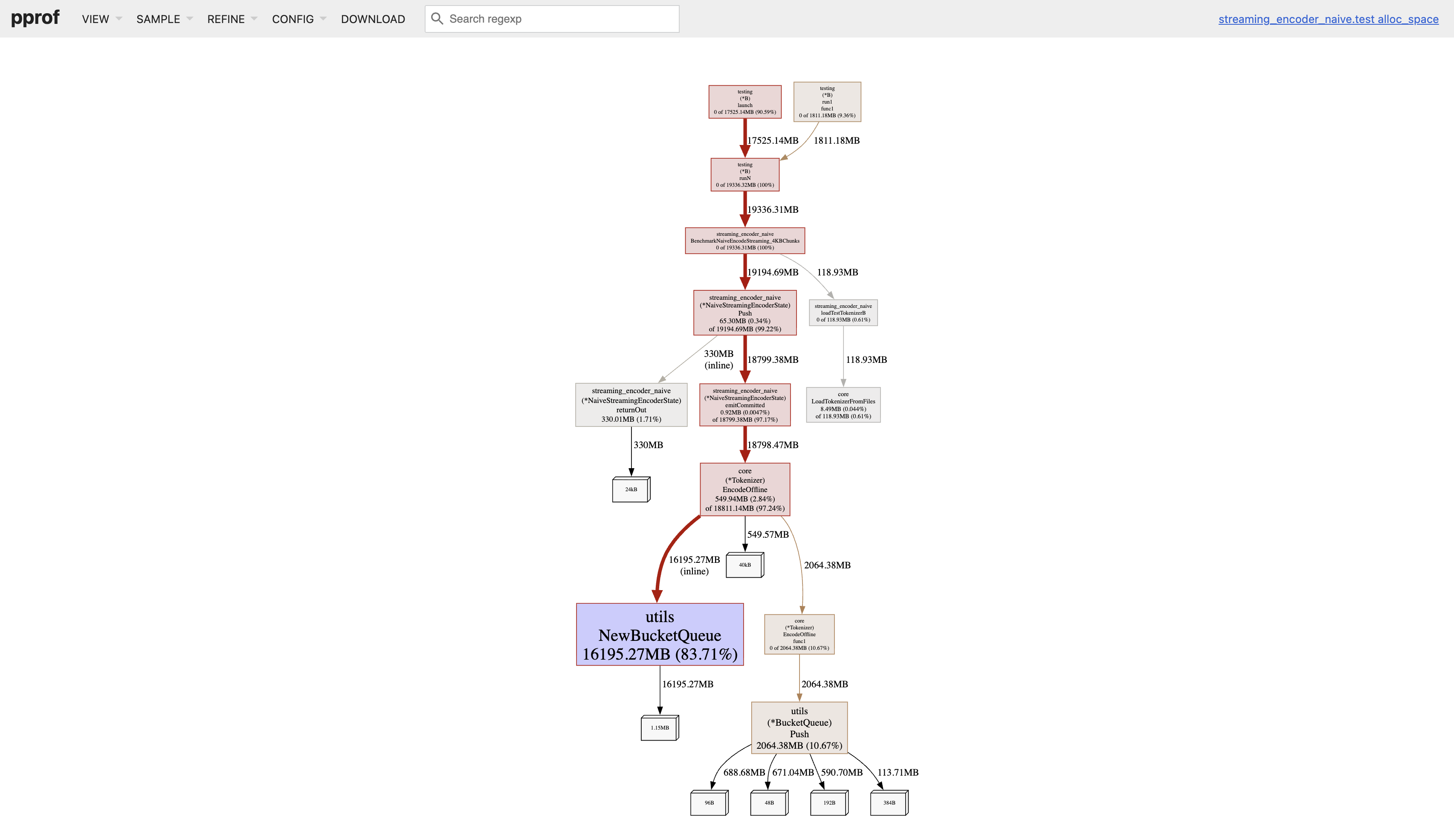

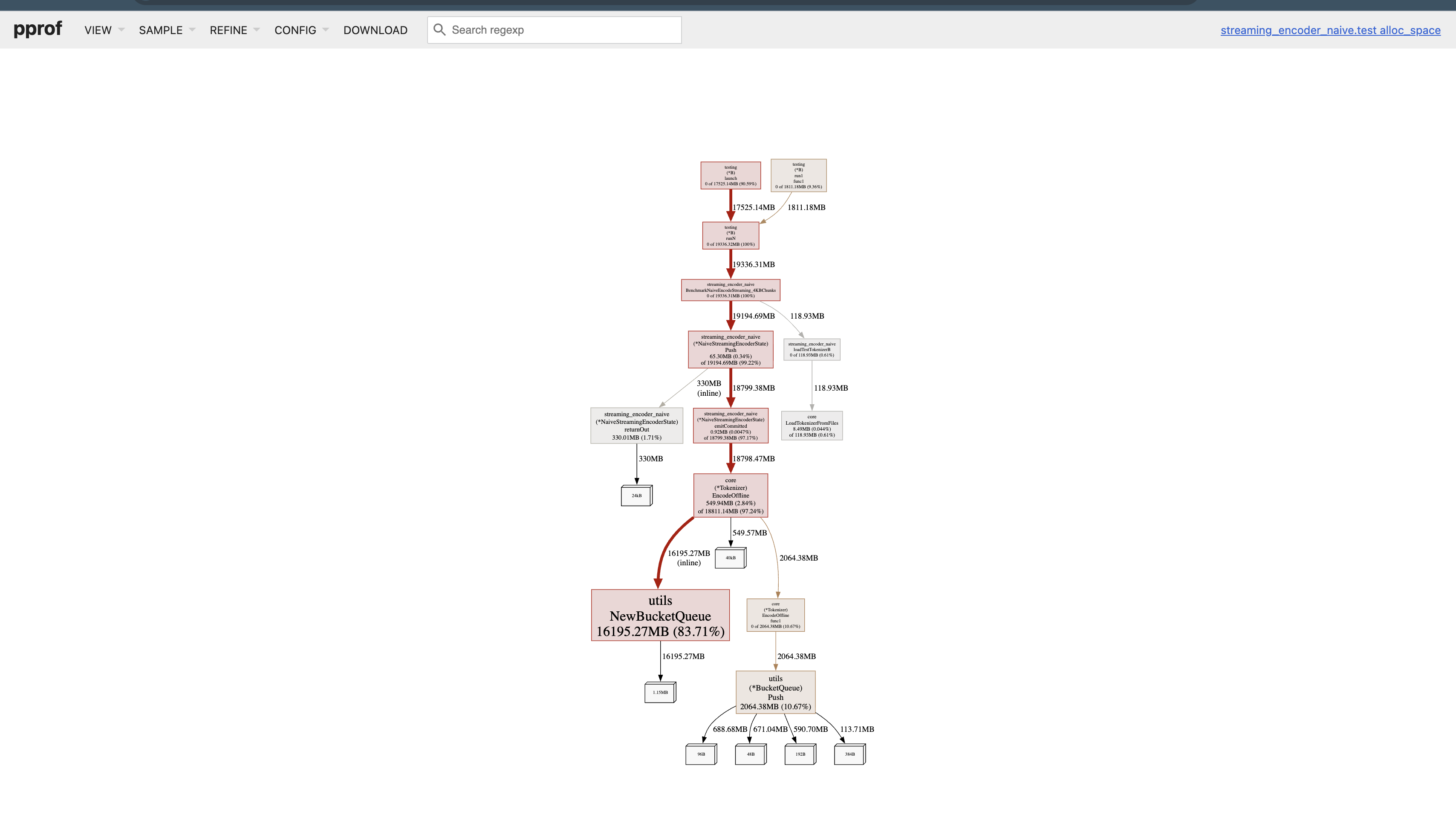

Here’s the memory flamegraph from the baseline naive streaming encoder (4 KB chunks, single-core).

~84% of all memory allocated during tokenization comes from constructing the BucketQueue itself. From what I gather,

- BucketQueue internally allocates one linked list per rank bucket

- GPT-2 BPE has ~50K ranks

- So the queue allocates tens of thousands of small slices / structs

- This results in millions of small allocations

At this point, I realized that BucketQueue is extremely memory-unfriendly and behaves catastrophically in Go’s allocator model.

Even if we ignore the allocations from constructing the queue (which we shouldn’t given the sheer volume), every push to the queue incurs:

- A fresh struct

- Repeated pointer chasing

- Occasional slice growth in specific buckets

Together these account for another 10% of total memory. The problem isn’t BPE, it’s the data structure.

Optimization #1: FastLookup

In the naive implementation, every time the encoder considers merging two adjacent tokens (a, b), it performs a lookup into a Go map keyed by (a << 32) | b. In a streaming BPE encoder, this happens thousands of times per 4KB chunk. Instead of hashing (a, b) on every check, we can trade a small, fixed amount of memory for a direct indexed lookup. We introduce a dense 2D lookup table for common merge pairs:

fastLookup[a][b] -> packed merge info

At runtime, lookup becomes:

if a < N && b < N {

info := fastLookup[a][b]

if info != sentinel {

return info

}

}

return fallbackMap[key]

The fast lookup table is sized (N, N). Increasing N increases the hit rate of the fast path and reduces fallback map lookups and in fact, larger values did produce additional speedups in experiments. However, for the purposes of this post, the goal is not to find a globally optimal cutoff, but to demonstrate an optimization pattern: replacing hash-based lookups in the hot loop with bounded, direct memory access. N = 2048 strikes a reasonable balance for illustrating the idea without introducing excessive memory overhead.

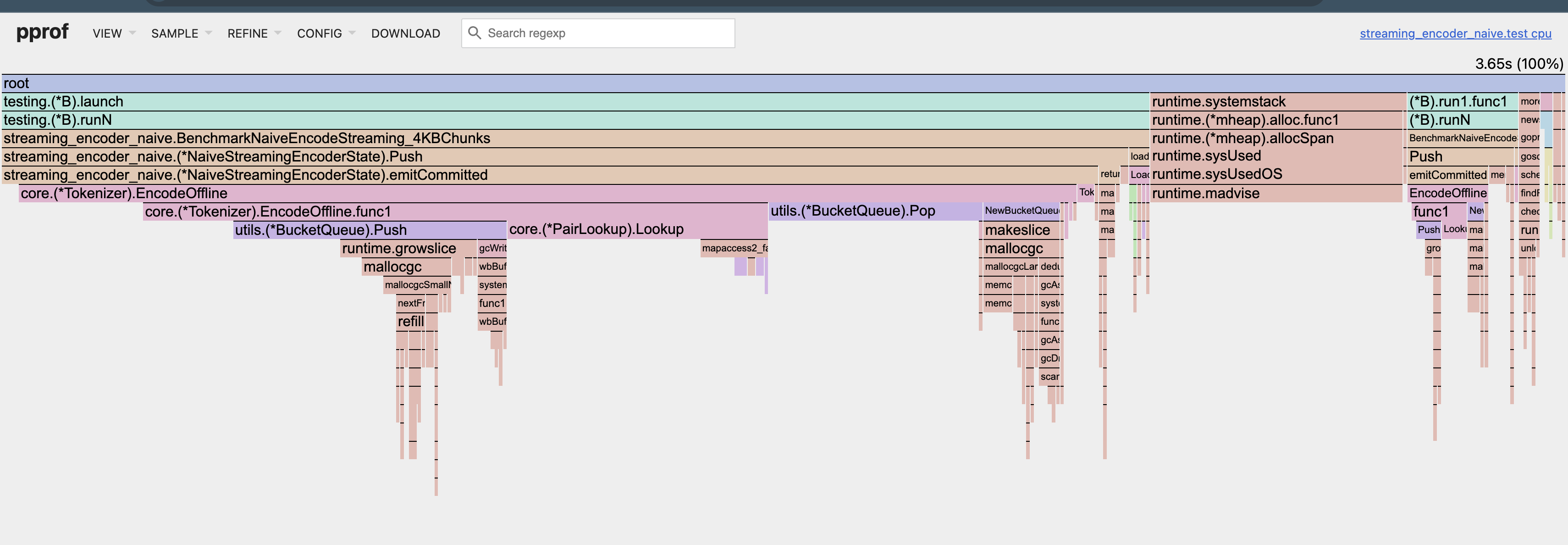

Here’s the CPU flamegraph after the first optimization of the naive streaming encoder (4 KB chunks, single-core).

Benchmark Results

Before:

540,239,550 ns/op

9.70 MB/s

1830942153 B/op

2343402 allocs/op

After:

383,143,150 ns/op

13.68 MB/s

1830926814 B/op

2343350 allocs/op

The Delta:

~41% faster runtime

~41% higher throughput

Allocation count: unchanged

B/op: unchanged (expected)

Optimization #2: Preallocating Scratch Buffers

After addressing pair lookup in the hot loop, the next source of overhead showed up before the merge loop even begins. Each call to the encoder rebuilds a set of internal scratch buffers: tokens, prev, next, liveVersion.

In the naive implementation, these slices are freshly prepared on every invocation, and Go helpfully zero-initializes all of them. Zeroing memory is fast, but not free and, in our case, it showed up as a small, but measurable, component of per-chunk overhead once the larger hotspots were removed.

The key observation here is that most of these buffers do not actually need to be cleared. During encoding:

tokens,prev, andnextare fully overwritten in the hot loop- only

liveVersionrelies on a known initial state, since merge-candidate liveness depends on it

and this makes it possible to reuse scratch buffers across invocations and avoid unnecessary zeroing. To optimize,we introduce two preparation paths:

sc.prepare(n) // baseline: full slice zero-init

sc.prepareNoZero(n) // optimization

Benchmark Results

Before:

383,143,150 ns/op

13.68 MB/s

1830926814 B/op

2343350 allocs/op

After:

380,274,475 ns/op

13.79 MB/s

1830930540 B/op

2343360 allocs/op

The Delta:

- ~1% faster runtime

- ~1% higher throughput

- Allocation count: unchanged

- B/op: unchanged (expected)

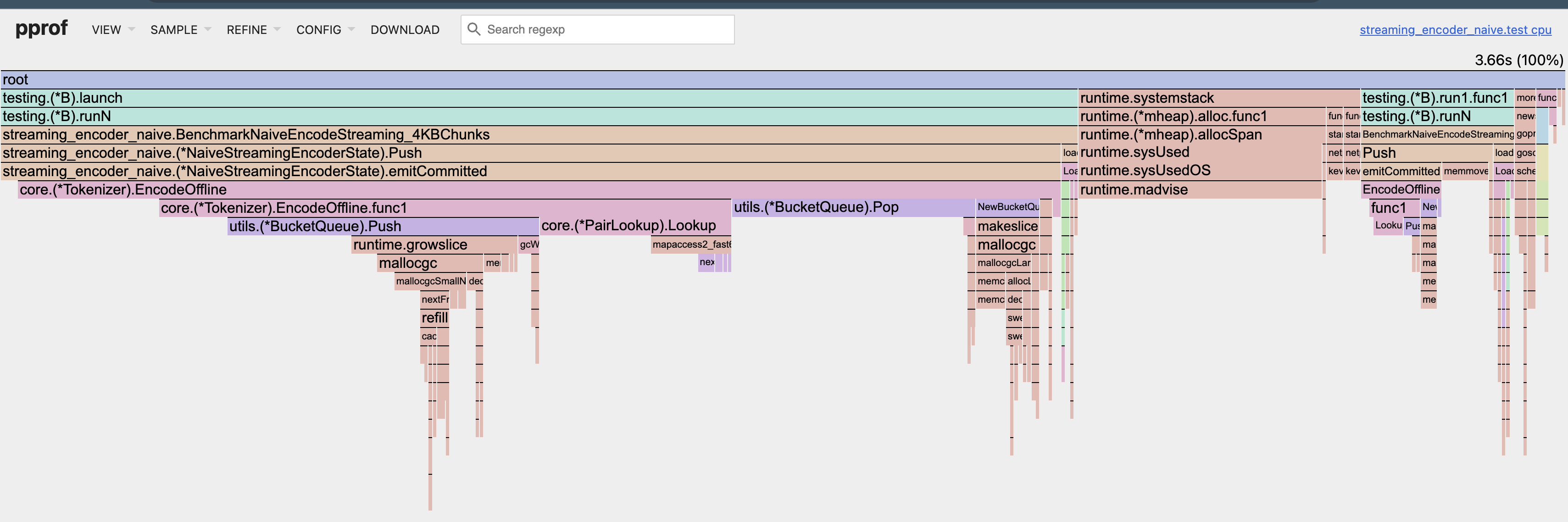

The CPU flamegraph shows a small reduction in runtime overhead associated with slice preparation and memory clearing.

This particular optimization doesn’t move the needle nearly as much as eliminating hash-map lookups, but it removes unnecessary work from a performance-critical path at essentially zero cost in complexity.

Optimization #3: Reusing the Output Buffer and Eliminating the Final Copy

Similar to the scratch buffer overhead, the next hotspot wasn’t inside the merge loop; it was at the tail of the algorithm, where we package and return the tokens. The naive version of the streaming encoder ended with this pattern:

out := make([]int, 0, n)

for i := head; i != -1; i = next[i] {

out = append(out, tokens[i])

}

return out

There are two main issues at play here.

1. A fresh buffer allocation every time

On every chunk, we:

- Allocate a brand-new slice

- Grow it via appends

- Touch memory that the GC now has to track

This is wasteful, because for streaming workloads the shape of the output is predictable. A 4 KB chunk is always going to produce output in the same ballpark. There’s no reason to allocate a new buffer each time when the old one works just fine.

So we replaced this with a reusable buffer:

st.outBuf = st.outBuf[:0]

st.outBuf = append(st.outBuf, tokens...)

If the preallocated capacity is large enough (we picked 64K), we avoid:

- new allocations

- slice growth

- GC pressure

2. A full linear copy of the final tokens

Even after we were done with all merges, we still copied the token sequence into a new slice before returning it. That’s a full linear pass over the data that adds nothing but latency.

So we introduced a simple switch:

if st.OptNoCopyReturn {

return st.outBuf // zero-copy return

}

out := make([]int, len(st.outBuf))

copy(out, st.outBuf)

return out

When OptNoCopyReturn is enabled, we skip the copy entirely and return a slice header that points directly into the reusable buffer.

For streaming workloads where the consumer immediately processes the tokens, this is perfectly safe and much faster.

The memory flamegraph shows a clear reduction in allocation pressure at the tail of the encoding pipeline, reflecting the elimination of per-chunk output allocations and copies.

The CPU flamegraph shows a small reduction in runtime overhead associated with allocation, slice growth, and memory copying. The core merge logic remains unchanged.

Benchmark Results

Before:

380,274,475 ns/op

13.79 MB/s

1830930540 B/op

2343360 allocs/op

After:

375,547,250 ns/op

13.96 MB/s

1799469576 B/op

2342068 allocs/op

The Delta:

- ~1.2% faster runtime

- ~31 MB less memory allocated per encode

- ~1,300 fewer allocations per encode

Putting it all together

Starting from a naive streaming BPE encoder, we incrementally applied three optimizations, each targeting a different class of overhead:

- FastLookup routed most merge-pair lookups through a bounded 2D table, with a fallback map for the remaining cases.

- Scratch buffer reuse trimmed redundant setup work before encoding begins.

- Output buffer reuse and zero-copy return eliminated avoidable allocations and copying at the tail.

Overall, compared to the baseline:

- ~44% faster runtime

- ~44% higher throughput

- ~31 MB less memory allocated per encode

- ~1,300 fewer allocations per encode

What surprised me most while working on this was that even after getting a correct, naive implementation of BPE in place, a lot of the remaining difficulty lived outside the algorithm itself. The tricky part was everything around it: how often certain paths execute, where allocations sneak in, and how small, reasonable choices compound when they sit in a hot loop.

Over the next few posts, I’ll zoom out from tokenization and look at KV caches and inference-time optimizations, and how those systems interact with tokenization in practice.